“And the Leaves of the Tree shall be for the Healing of Nations”

Revelations; 22.2

In recent decades, a new chapter has been added to the yew’s relationship with humankind. It tells of the unprecedented healing of millions of people in nations spread all over the world by a medicine extracted from the unique biochemistry of yew trees.

The leaves (or needles) of Taxus bacatta have been well known to be extremely highly poisonous since prehistory. They are a mortal danger to humans and horses and cattle if the animals browse freely upon yew leaves. However, yew foliage in small, carefully measured amounts is known to have been added to cattle fodder especially during hard winters. Rodents and herbivores such as rabbits, deer and sheep browse upon yew leaves and bark with apparent impunity. This perhaps may not necessarily be only for food, as the leaves and bark have little nutritional content, and may also be a self-medication process, such as when cats and dogs eat plants for the same reason. Often yews are browsed when better food sources are local and plentiful. Mice, voles and birds, such as the Blue Tit, open yew seeds to eat the kernel.

Herbivore damage to yew seedlings but which has not yet killed them

Yew seeds are toxic to humans, but the red fruits of the female yew are edible after first removing the seed. These arils, so called as they are not berries, are very sweet when ripe possessing a honey like taste. They have a high calorific value useful for birds (e.g. thrushes) and animals (e.g. foxes and badgers) as autumn and winter food. Thrushes, blackbirds, redwings and fieldfares eat the arils whole, and it is suspected that yew seeds have a better chance of germination if they have passed through an avian digestive tract and excreted within a handy dose of fertiliser.

Taxus baccata foliage, however, being so toxic to humans and valuable livestock is one reason why the yew is associated with death. In Greek Classical cosmology, the goddess Artemis punished transgressors against Nature by shooting them with arrows tipped with poison brewed from yew leaves– in other words her ultimate deterrent was an inescapable sentence. The use of yew wood to create that most efficient and deadly killing tool for hunting and warfare, the longbow, also meant the yew had a life-taking and death-bringing reputation. Shakespeare in his play Macbeth (Act 4 Scene 1, Page 2) describes the use of yew as an essential ingredient of a poisonous witch’s brew. It even became believed that to sleep under a yew risked death. (For more on the Macbeth link see article on Glamis Castle)

Yet in many cultures across Eurasia, moreover for millennia, the yew has been celebrated as a Tree of Life, a sacred tree (see What’s in A Name article) associated with various gods and goddesses, religions and also emperors, kings, queens and particular royal dynasties. Obviously, this may be because the yew is commonly so long lived and was observed possessing an extraordinarily strong life force, vitality or life essence which is a necessity to live for so long. But is that all? Or is there something else about the yew that caused cultures to perceive and experience the yew as a Tree of Life for reasons more than its longevity. Moreover, something extraordinary which resulted in associating it with the divinities which created and controlled life, and the temporal earthly powers of monarchies and religions. Something tangible and significant but unquantifiable and involving more than the ‘mere’ material experience of yew trees seems to be going on here.

Despite this cross-cultural regard for the yew possessing an extraordinary capacity of ‘life’ and featuring in the history of diverse nations, and the lives of emperors, dynasties, kings, queens, saints and bishops, over the centuries of the post Christian period, the perception of the yew in western cultures became increasingly macabre and associated with the ‘finality’ and fear of death. To many the yew became a dark, gloomy, dread presence, poisoning and haunting rather than blessing churchyards and other sacred places. The esteem it once held in many spiritual beliefs diminished further with the coming of Protestant Christianity, the infamous witch hunts and the literary and poetic genre of Victorian Gothic. The yew was gradually subsumed and relegated to shadowy places in people’s minds, becoming associated with witches, the devil and yew roots seeking out the mouths of corpses to feed on their souls. Yet not long before this period the yew was used and celebrated in Catholic church rituals such as Palm Sunday and Ash Wednesday. Instead of the material essence of the ‘Tree of Life’ and the non-material spiritual and sacred significance of the yew being celebrated anymore, a mythical monster was spawned, the Tree of Death. Even today many people are wary of going anywhere near this ‘poisonous’ and ‘noxious’ tree, showing how deep these erroneous superstitions have reached. In fact:

“Fatal poisoning by yew leaves in modern times is generally very rare. The only fatalities recorded in recent history are associated with the intentional ingestion of the sap or leaf by adults.” (3)

Yet, despite these associations with death, the reputation of the yew as a Tree of Life took an entirely unexpected turn in the mid-20th century and stemmed from an unlikely and statistically somewhat miraculous source.

Medical science discovered that the yew contained alkaloid chemicals (taxines) and volatile oils with unique anti-cancer properties resulting in the development of the drugs Taxol, and the later refinement Taxotere (both registered trademarks). This medication has saved millions of lives worldwide, including considerable thousands in Britain. But how many patients know their lives have been radically improved, or saved, thanks to a nondescript evergreen tree they may even pass by around where they live? Many patients successfully treated and recovered have only discovered the link to the yew by their own curiosity researching their treatment’s origins and then discovering where it comes from.

In 1964 the yew was the only plant source, from over 30,000 plants tested by the National Cancer Institute of the United States, to provide a treatment breakthrough in the battle against cancer when it seemed all hope was lost. The NCIUS program, launched in 1958, had seen no successful results during the previous six years of research. Then a substance which gave some hope was initially extracted from the bark of the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) in the north western USA and named Taxol (1). It proved to be highly effective against specific forms of cancer of the ovaries, breast and lung, as well as drastically reducing needs for surgery or chemotherapy.

Then began the decimation of yews in the USA as Pacific yews – a ‘trash tree’ in North American forestry terms – were flayed for their bark to harvest the extract, by now named paclitaxel, and the resulting dead stumps mainly slashed and burned. This process killed yews in their hundreds of thousands in the Western Pacific coastal forests of the USA. By the 1990s, processing yew foliage by improved extraction methods instead of using bark, achieved better results, yielding a more powerful substance called docetaxel. This gave rise to looking at sustainable harvesting methods due to regional Pacific yew populations in ancient and old growth forests being decimated before this discovery was made. The voracious and rapacious demand for yew foliage went global and following on from the massive harvesting of bark has resulted in a terrible cost for the yew. Populations in the USA, Himalayan regions and Asia have been so badly hit by defoliation and felling in the last fifty years it has seen extinctions in many areas – a total loss of millions of yews in what is a blink of an eye in historical terms.

Some British yew sites with stately homes and extensive hedges or topiary, such as Longleat House, Wiltshire in England, now sell annually cropped yew clippings to the pharmaceutical industry. Even if this is a sustainable resource, it is merely a tiny contribution to the vast demand. Unfortunately, it is not the first time that yews have suffered to almost unimaginable extents meeting demands made upon it by humankind. The military need for yew wood to make the best longbows from the 11th to the 16th century wiped out millions of yews in most of western Europe and in many of those areas it has never returned.

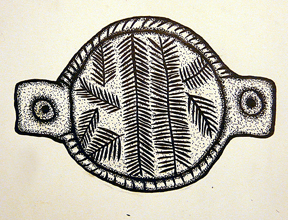

The fact the yew possesses such extraordinary and unique healing effects, against arguably the most commonly feared of diseases, surely justifies that despite its toxicity, medicinally it is an extraordinary ‘Tree of Life’. But it is not perceived nor valued in this way as its cultural history deserves – as a special and sacred tree – in the perceptions of modern pharmacology. How could it be when the yew has been slaughtered to the extent it has in the last five decades to feed the appetite of the pharmaceutical industry. However, that the yew possesses potent anti-cancer powers, in this case against abdominal cancer, was recorded by the Vedic culture in India 1,400 years ago (2) On a prehistoric pot lid from Mesopotamia are depictions of yew foliage looking as if real foliage was pressed into the wet clay before firing. Was this decoration or a label for what was kept within? Or both? And if specifically used for storing yew foliage, perhaps made into a salve, or dried for creating a potion, some beneficial medicinal properties of yew were also known in the prehistoric Middle East? Could it have been a ritual object used in a specific ceremony perhaps involving healing?

Modern medical science has not discovered but in truth rediscovered knowledge of the ‘Tree of Life’ healing qualities of the yew as utilised 1,400 years ago (at least) in India and, no doubt, with the utmost respect for the tree itself, and the healing it provided. There was no need to flay a yew of its bark, nor strip its ability to photosynthesise to fatal levels by unsustainably harvesting needles. Yews did not have to die to provide life-saving medicine for people. But western pharmacopeia seems to have had nowhere near the Vedic insights of the yew’s healing qualities, as using yew in western medicine often involved creating a life-threatening abortifacient concoction which often killed the mother as well as the foetus, or as a way of poisoning enemies. It had no real renown for having life giving properties.

Yet yew was, and is, used for healing by many tribes of indigenous people today. In North America it is used as sacred medicine for a variety of ailments and has been for many thousands of years.

“Whereas other species of yew trees around the world are poisonous, the American Pacific yew is a rare and special plant which is non-toxic and has for untold centuries, provided medicinal benefits, not only to humans, but to animals as well.” (4)

Yew herbal dietary supplements and skin treatments created from sustainable sources of Pacific yew now extends beyond its use by indigenous people and is now generally available (see link below).

If a person with experience of the yew’s healing qualities perceives a living yew, how could it possibly be perceived by that person as being ‘just’ a tree? It would surely be perceived as so much more than a disposable resource, and perhaps perceived and experienced instead as ‘something’ indescribable and tangibly felt by something more than just five senses working in combination. If not, names for the yew such as the Tree of Life, Tree of God or Divine Tree would not be what they represent – when the yew is experienced as ‘sacred’ and ‘otherworldly’ and possessing an indefinable ‘something’ which can be tangibly experienced. Moreover, when the yew is appreciated as a healing tree – a Tree of Life – first and foremost and not a poisonous, death-dealing tree. Furthermore, providing healing not just for the body but the mind, spirit and soul as well (see Charubel poem).

Many, many people experience a time of solace from their various troubles and challenges by regularly spending time with trees, often particularly favourite trees, and have experienced their own inspirations, insights and revelations as a result. Favouring yew trees for this purpose is common, as they provide ideal shade and shelter all year round, and often in quiet and beautiful churchyard or parkland surroundings – encouraging perception, introspection, meditation and prayer. If a yew has layered, or has not lost any of its lower branches, the space within its canopy easily conjures the feeling it is a ‘natural temple’, which was how William Wordsworth describes the grove of the Borrowdale Yews in Cumbria, England in a poem from 1803 (see page on Wordsworth yew-tree poems).

This solace ideally provided by yew trees may also be of unquantifiable assistance to mental well-being, and something many people have described from personal experience works for them, even though there may be no clear, concise and rational medical explanation. The experience, effect and beneficial health results, however, are prime evidence whether explainable or not, that there can be no placebo effect here, there is no experimentation, no artificiality. Instead, there is a dynamic interaction happening between a person and a tree often manifesting in an ‘healing’ experience – sometimes via a distinct spiritual experience – for the person concerned. Something real is happening here, however inexplicable it may be, under the leaves of the yew tree and, moreover, something unprescribed by any pharmaceutical companies.

In more poetry from William Wordsworth about yew trees:

“Nay, Traveller! rest. This lonely Yew-tree stands

Far from all human dwelling: what if here

No sparkling rivulet spread the verdant herb?

What if the bee love not these barren boughs?

Yet, if the wind breathe soft, the curling waves,

That break against the shore, shall lull thy mind

By one soft impulse saved from vacancy.Lines 1 – 7, from Lines Left Upon A Seat in a Yew Tree……

Furthermore, there is no physical ingestion of the yew involved in these circumstances, it is simply ‘being’ with the yew – interacting and resonating with its electro-magnetic field so to speak – which works in positive, beneficial and healing ways for many people. One of the many examples of famous historical characters seeking privacy with yew trees was St Columba, who constructed a personal cell for prayer and contemplation in the 6th century under a great yew on the Isle of Bernera, in the Firth of Lorne off western Scotland. This yew was felled in the 18th century by the local laird for building material at the mainland castle of Loch Nell but was discovered in the mid-20th century to be regrowing from the stump in a terrain hugging, creeper like growth habit.

In view of the ancient and intercontinental use of yew as a treatment for a variety of ailments and diseases, modern Western science has only very recently re-discovered, not discovered, the beneficial medicinal powers of the yew which had become so occulted in the west by ignorance, hysteria, religion and superstition. It is literally the case now that leaves of the yew have produced life-saving healing for people in nations all over the planet by the discovery of Taxol. What other knowledge of the yew has also been obscured, almost lost and could be awaiting modern rediscovery? Let us recall the yew was the only plant from 30,000 tested that gave hope for a successful anti-cancer treatment. It had ‘something else’ no other plant or tree tested had and attacked cancer cells in a different and successful way which nothing else did. Here again is a demonstration of the singularity, the uniqueness of the yew putting it in a class of its own.

The quote above from the Book of Revelations of course does not refer to the yew. However, it is clearly compelling the yew does fulfil the literal meaning of those words. Whilst finding that one of the most toxic trees in the world had extraordinary healing qualities certainly came as a revelation to 20th century medicine. Unfortunately given such a revelation concerning the yew, it is a sad indictment of a response to this gift of knowledge that for the yew the consequences of this exchange have been catastrophic. What has provided life for people and huge profits for the pharmaceutical industry has meant death for the yew to devastating levels. It is not just the huge numbers involved and the greater effect on a variety of biospheres suddenly losing yew trees, but also wiping out yews at such scales reduces genetic diversity by less male yews pollinating fewer female yews, and hence compromising the production of new genetic mixes in the seeds.

In the north west USA, China, Taiwan, the Philippines and India tens of millions of yew cuttings are raised in greenhouse conditions, an effort to replace the now unsustainable natural resource with something somewhat sustainable, such is the ongoing and increasing demand from the pharmaceutical industry. (5) This was an emergency response to natural populations of yew being obliterated in regions supplying the trade. It also created the need to synthesise the chemicals extracted from the yew, taking away the life essence in the process, the very essence which creates these unique chemicals. However, synthesising the Taxol molecule was presented with a serious problem.

“The taxol molecule was incredibly complex making it almost impossible to copy its structure in the laboratory (which is the process used in creating synthetic drugs). In order to make a synthetic drug from a natural substance, scientists must first be able to ‘see’ its molecular structure. One of the processes which is used to provide a picture of the crystalline structure of a molecule so that it can be copied under laboratory conditions is known as X-ray crystallography. But in the case of the taxol molecule, its crystals were ‘invariably fine needles that were unsuitable for X-ray structure determination. This is still true 30 years later, as no reports of the X-ray crystal structure of taxol itself have yet appeared (Taxol, Science and Applications, Matthew Suffness.’ ” (6)

In China, the yew is associated with the goddess of compassion and mercy Kuan Yin, but there has been no compassion and mercy shown to the yew since it recently revealed its unique medicinal secret to the global pharmaceutical industry. An extraordinarily special tree is now intensively farmed in cloned populations like any production line of animals living out their lives on a factory farm, devoid of natural light, air and water and with roots disconnected from the Earth itself. It is not only in China, far from it, that the yew’s place in human perception recognition and experience has fallen so far. In Britain, if a yew gets in the way of ‘progress’ or land development, even if it is in a sacred space, there is little or nothing to effectively protect it. It has no special value, no worth and no esteem, appreciation, or respect to prevent any demise. It is certainly not perceived or appreciated as a ‘Tree of Life’.

If we look again at ‘and the leaves of the tree shall be for the healing of nations’ perhaps there is another interpretation of subtle meaning beyond the literal. It does not say that the leaves of ‘a’ tree are significant but the leaves of ‘the’ tree, implying there is a tree which is unique, standing apart from all others – ‘The’ Tree. This may well refer to a symbolic tree and hence we do not think that such a legendary tree could really exist. However, given the sacred epithets for the yew such as God’s Tree and Divine Tree, they clearly imply that the yew is unique, it is ‘the’ tree that stands apart from all others.

This is not in a hierarchical sense with the yew at the top and all other trees beneath it, merely acknowledging that the yew is in a class of its own. It is ‘something else’ and this perspective reflects our experience of it throughout human evolution, not only in modern scientific investigation but also in cultural and metaphysical circumstances spanning tens of thousands of years. Furthermore, the yew clearly proved it was ‘the’ lifeform from over 30,000 tested which gave what is the essence of the words in the Book of Revelations – hope and healing. Hope in the battle against cancer and healing via a super drug extracted from the yew’s extraordinary molecular structure which could not be provided by the other plant species tested. This hope and healing became a genuine revelation, that from the unlikeliest of sources, the fatally toxic ‘Tree of Death’, came such a gift of life. Hopefully, this truth will give a new vision and appreciation of the yew, and that it has, is, and always will be, in itself, a Tree of Life. It has never been a Tree of Death, except when misunderstood and labelled as such by ignorance and superstition.

The yew has provided life both in terms of extension and quality to those who have received its medicine – and it takes a potent medicine indeed to have such spectacular and miraculous results. Perhaps certain animals like deer are indeed aware, after all, of the yew’s potent medicine found in its needles. However, the leaves of any tree are a product and manifestation of the entirety of the tree – roots begetting trunks, branches begetting foliage, flowers, fruit and seeds. What is in the essence of life flowing throughout the entirety of the yew produced the unique anti-cancer treatments, clearly a ‘life force’ which 30,000 other plant species living on Earth do not have in the way the yew has it and especially the Pacific yew, the source of the scientific revelation.

This amazing aspect of the yew is modern evidence why the yew’s identity as a Tree of Life, or rather as ‘the’ Tree of Life, in so many cultures and for so long genuinely acknowledges the uniqueness of the yew as a self-evident conclusion. It has, and lives, a life like no other plant or tree and from that life has genuinely come the revelation of discovering a unique healing for the people of many nations from the unique biochemistry – the life – within the yew tree.

References:

(1) Hageneder, Fred: Yew A History, p. 111, History Press, 2011

(2) Hageneder, Fred: Yew A History, p. 88 – 91, History Press,

(3) Bevan-Jones, Robert: The Ancient Yew, 3rd edition, p. 8, Windgather Press, 2017.

(4) Christy, Martha M: The Pacific Yew Story, How an Ancient Tree became a Modern Miracle, Early Medicinal Uses of Pacific Yew p. 15 – 17, Wishland Publishing Inc., Arizona, USA 1999.

(5) Christy, Martha M: The Pacific Yew Story, How an Ancient Tree became a Modern Miracle, On the Trail of the Natural Source, p. 13, Wishland Publishing Inc., Arizona, USA 1999.

(6) Christy, Martha M: The Pacific Yew Story, How an Ancient Tree became a Modern Miracle, On the Trail of the Natural Source, p. 7, Wishland Publishing Inc., Arizona, USA 1999.

For enquiries into yew dietary supplements, yew tea and skin treatments contact Bighorn Botanicals Inc. at www.bighornbotanicals.com